-By LeN Legal Correspondent

(Lanka-e-News -02.Nov.2025, 11.40 PM) It was a dark Saturday evening — October 22, 1988 — when three young men, returning from a Student–Parent Association meeting in Ratnapura, vanished into the shadows of Sri Lanka’s political violence.

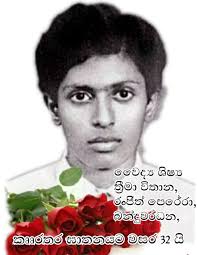

They were Padmasiri Trima Vithana, Ranjith Perera, and B.D. Bandhuwardhana — bright, idealistic student activists committed to protecting free education from privatization. They never made it home.

Near the Ratnapura bus stand, witnesses recall a white Pajero jeep screeching to a halt. Several men jumped out, dragging the three students inside before speeding away into the night. The vehicle, villagers later whispered, belonged to the son of a powerful provincial politician.

The next morning — Sunday, October 23, 1988 — a farmer from Wellawaya stumbled upon a horrifying scene. Three mutilated bodies lay near an irrigation canal. Their nails were pulled out, cigarette burns covered their skin, and a large iron nail had been driven into one victim’s skull.

“I thought they were animals first,” the farmer later told police. “But then I saw the badges from the student union.”

That discovery triggered what should have been one of the most significant murder investigations of the late 1980s. Instead, it became a textbook case of justice denied through political interference.

It took a full week before the case resurfaced. On October 26, 1988, a special police team finally arrested Susantha Punchnilalme, the son of the then Chief Minister of Sabaragamuwa Province.

He was charged with the abduction and murder of the three students.

But the case was crippled from the start. Key witnesses went missing. Forensic samples were “lost.” And the prosecution failed to provide critical evidence during trial.

Although the Monaragala Magistrate B.S. Jayasekara had issued clear instructions to preserve the bodies and forward them for postmortem examination, that process too was tainted by bureaucratic negligence.

Dr. Thiswarampillai, the district medical officer who conducted the first inquest, confirmed that the bodies were later transferred by helicopter to the Colombo Medical Faculty. There, the Judicial Medical Officer, Dr. M.S. Lakshman Salgado, carried out two separate examinations. His findings were chilling — both feet of the victims had been severed post-mortem, their hands mutilated, and four bullet wounds were detected.

Yet, despite such gruesome evidence, the case collapsed on “technical grounds.”

In a controversial ruling, High Court Judge K.T. Chitrasiri discharged the accused, citing procedural irregularities and insufficient prosecution evidence. No appeal followed. The file was quietly shelved.

According to several former officials now speaking publicly, the 1988–89 period was one of state-sponsored abductions and extrajudicial killings.

At the time, Sri Lanka was in the grip of violent insurrection and counter-insurgency under President R. Premadasa.

Witnesses claim the orders to “remove student agitators” in Ratnapura came from then State Defence Minister Ranjan Wijeratne, who reportedly visited the Ratnapura district days before the abductions.

Declassified intelligence documents now reveal that several student leaders were marked for elimination for opposing the White Paper on Education — a UNP policy move seen as the first step toward privatizing universities.

The three victims were part of the Student–Parent Solidarity Movement, a grassroots organization that lobbied to protect free education — a principle enshrined since the 1940s.

“They were not insurgents,” said Dr.Jayasundara, a former teacher and activist who attended the same meeting. “They were students demanding fairness. For that, they were tortured and killed.”

The suspect, Susantha Punchnilalme, went on to face further allegations years later, including the murder of MP Nalanda Ellawala, who was shot dead in Kuruwita, on 11th February 1997, during a political rally,

Observers say that had justice been served in the Trima Vithana case, the later political assassination could have been prevented. “When a system lets one man escape accountability for killing students, it signals that power trumps justice,” noted retired magistrate Seneviratne.

Now, nearly four decades later, several witnesses who were silenced or went into hiding during the 1990s have come forward under the new NPP government’s whistleblower protection framework.

Among them are a former police constable and a local transport worker who both claim they saw the Pajero jeep parked outside the Ratnapura Rest House that night. Their testimonies could reconstruct the entire sequence of the abduction and identify accomplices previously uncharged.

Human rights organizations and legal reformists are now urging the Attorney General’s Department to reopen the file and conduct a retrial under international fair trial standards.

“This case is not merely a murder investigation,” said Attorney Dissanayake, who is preparing a new petition. “It’s a test of whether the Sri Lankan state has the courage to correct its historical crimes. These young men were tortured, mutilated, and discarded — and the system rewarded their killers.”

For the National People’s Power (NPP) administration, which came to office promising transparency, truth, and justice, this case represents a defining challenge.

These students, activists say, laid the moral foundation of the modern NPP movement, standing up against the authoritarianism of the late 1980s.

Their deaths were not collateral damage — they were political executions designed to crush dissent and the right to education.

“Every policy victory we have today,” said student union leader Wijesooriya, “was paid for by their blood. The least this government can do is reopen the case and give them justice.”

Under international humanitarian law, and particularly under Article 15 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), a retrial is justified where the original proceedings were manipulated by political authority or when new evidence surfaces.

The NPP government, through its Ministry of Justice and Human Rights Commission, now has both the moral legitimacy and legal authority to act.

Legal experts argue that the retrial should not be limited to Susantha Punchnilalme alone, but should also examine chain-of-command responsibility, including those who allegedly gave orders from Colombo.

Thirty-seven years on, the ghosts of Ratnapura still whisper the names of Trima Vithana, Ranjith Perera, and Bandhuwardhana.

Their story is not just about three students—it is about a generation silenced for daring to speak.

If Sri Lanka is to claim the title of a democracy governed by law, the retrial of the Trima Vithana murder case must not be a slogan, but an act of national conscience.

Because justice delayed is not only justice denied — it is justice betrayed.

And betrayal, unlike time, never truly fades.

By LeN Legal Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-11-02 18:58:05)

Leave a Reply